If there’s one thing that the UK excels at, it’s the preservation of its history though the good work of the National Trust. Wild coastlines, historic trade infrastructure, manor homes, all at risk of loss to a developer’s wrecking ball are instead painstakingly maintained, protecting habitat and providing a glimpse into a way of life long since past. Himself and I are big fans indeed.

Whilst we navigate France by its Les Plus Beaux Villages, in England, the National Trust guides our way. And so it does today, at the beautiful Kingston Lacy, home to the Bankes family for over 300 years.

They clearly had an eye for good real estate – prior to Kingston Lacy, the family held Corfe Castle. Lady Mary Bankes held off an attack on the castle for three years during the English Civil War in the 1600s, successfully securing the family fortune thereby enabling her son to build Kingston Lacy. Sadly, Corfu Castle was destroyed in a later battle. In her spare time she popped out four sons and six daughters. She’s honoured at the entrance holding a sword and the keys to the castle. What a woman, centuries ahead of her time.

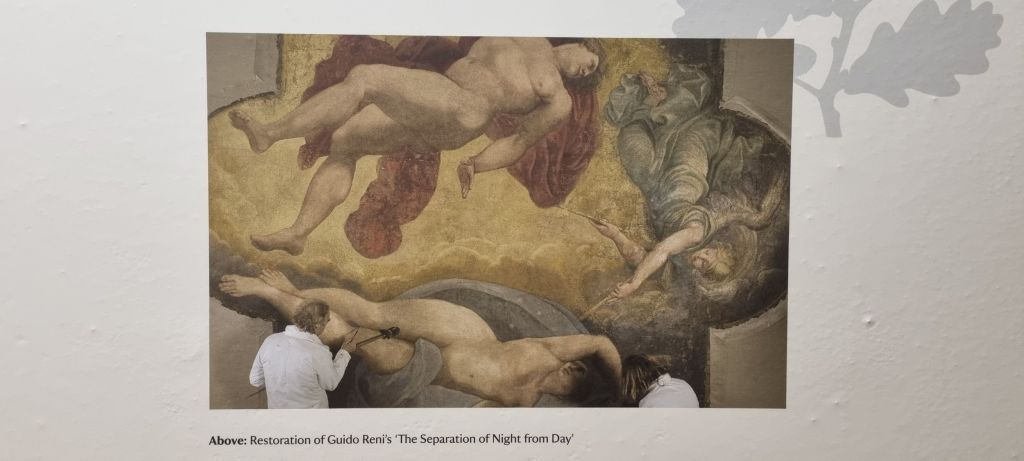

Much of Kingston Lacy’s flamboyant style is thanks to a later successor – William John Bankes transformed Kingston Lacy around 180 years ago, travelling through Europe collecting antiquities and adding to what was already an extensive art collection. Collected over 370 years, it features works by Ruebens, Van Dyck, Titian, Tintoretto and Velasquez. The collection is registered as a museum and is formally curated.

There’s even an extensive collection of Egyptian antiquities, extending to several obelisks installed throughout the garden. This period fascinates me – when one could travel to far flung lands and simply…take things that caught one’s eye, despite their being thousands of years old. How did that ever happen?

The house is over the top fabulous with themed rooms setting off the collection to best advantage. It even has an organ – there’s something you don’t see every day.

Particularly flamboyant is the Spanish Room, so named for its art. Once even brighter, the embossed leather walls originally shone with a gilt finish.

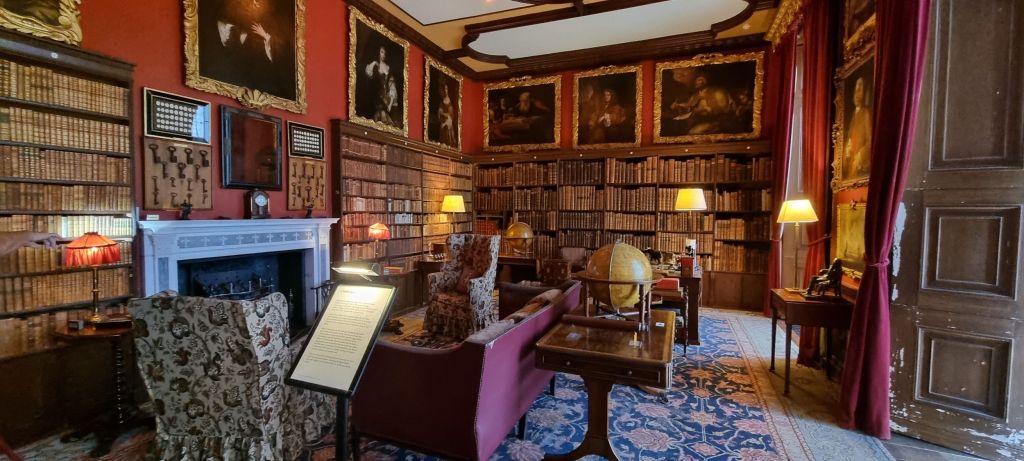

As always, the library is my favourite room. Oh for a lifetime to become lost in books held in major house libraries. All one would need is a plumply cushioned chair and a little cat for company. Perhaps a bell to ring for tea every so often. Bliss.

We wander for a while and eventually make our way to the grounds. If the house shines thanks to William Bankes’ skilful eye, the grounds owe their beauty to Henrietta Bankes. She managed the estate in the 1900s, transforming the gardens, ensuring the estate made money (cattle I believe) and entertaining royalty. She’s immortalised below – quite the glamour puss isn’t she, a famed beauty in her day.

We walk through the autumnal colours of the Japanese garden featuring cherry and maple trees and a Japanese tea garden.

The Philae Obelisk, discovered by William, took a 6 year journey to England to stand proudly opposite the manor.

The grounds cover 16,000 acres, that’s not a typo, 16,000 acres. It’s huge and includes formal gardens, lengthy woodland trails, parklands, a fernery and a series of avenues each featuring a single type of tree.

There’s a walled kitchen garden of course, which once provided for the household and its staff. It has an extraordinary range of heirloom plantings and glasshouses. A seperate well provides the garden’s requirements. I’m quite pea green with envy.

In their hey day, these houses really were small villages in their own right. We walk for ages and see but a fraction of what’s on offer. As usual, I have to be dragged away. Once I fall in love with a place, my off button mysteriously disappears. Himself applies the brakes gently but firmly. He’s had enough and off home we go.

I do love these National Trust sites – they never disappoint. Kingston Lacy passed into the hands of the Trust in 1981 ensuring its preservation for future generations.

I learn later that Willam fled England in 1841 to escape a homosexuality conviction, then punishable by death. Death. Unbelievable. True to form, he continued his travels and collecting, sending pieces home to his sister with explicit instructions for their display. Thank goodness he did. And thank goodness we’re a little more enlightened in the 21st century.